Integrating Pediatric Sleep Health Into Clinical Practice

Children have to eat. Children have to breathe. Children have to sleep.

Sleep is not optional and it is not a luxury. Sleep is a critical health asset required for optimal physical health, mental health and development.

As a pediatric sleep psychologist and researcher, I have focused much of my career on sleep problems. However, by talking about sleep health, we develop a better understanding of what is (and is not) a problem, as well as support pediatric health promotion and prevention.

The original definition and model of sleep health did not include pediatrics. Thus, we published a paper in 2021 that discussed the unique aspects of pediatric sleep health.

The following provides considerations and tips about pediatric sleep health for your clinical practice.

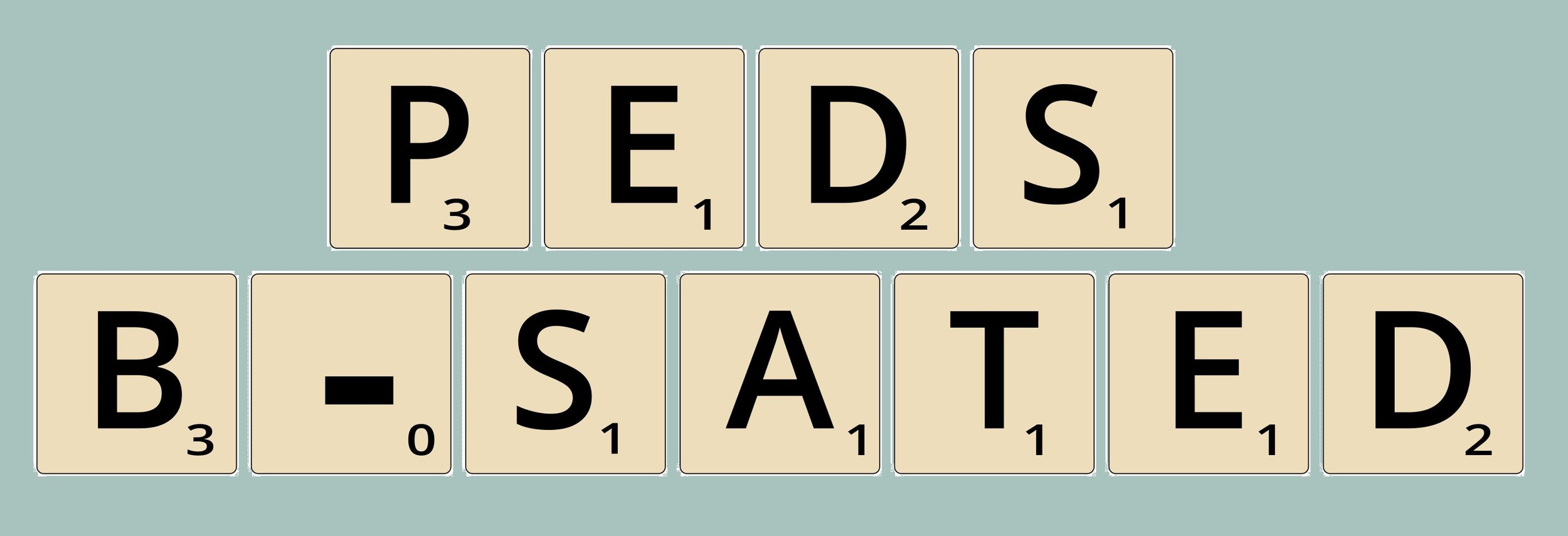

Sleep health is not simply the number of hours of sleep a child gets each night. Instead, sleep is a complex behavior with multiple dimensions, as conceptualized by the Peds B-SATED model.

For Pediatrics, sleep health includes: sleep-related Behaviors, Satisfaction with sleep, Alertness during waking hours, Timing of sleep, sleep Efficiency, and sleep Duration.

Sleep-Related Behaviors

Bedtime Routine

A consistent bedtime routine is one of the most important behaviors that promotes sleep across development. Although our technology shuts off with the touch of a button, our brains and bodies need time to transition from wakefulness to sleep. A consistent bedtime routine provides children and adolescents this transition. Bedtime routines should be short, with the same steps every night, always moving toward the place where a child sleeps.

*A bedtime chart with pictures showing the steps of the routine can make this transition easier for young children or children with neurodevelopmental disorders.

Caffeine

Caffeine is a stimulant that can interfere with both falling asleep and staying asleep. With a half-life of 4 to 6 hours, caffeine consumed in the afternoons or evening can still be buzzing in the brain at bedtime. This can result in children and adolescents taking longer to fall asleep, and in turn, not getting enough sleep. Some people are more sensitive to caffeine than others, with studies showing that even if caffeine is only consumed in the morning, it may still impact nighttime sleep quantity and quality.

*Children under 12 years should not consume any caffeine or energy drinks, and children ages 12-17 years should limit caffeine to less than 100 mg of caffeine per day.

Satisfaction with Sleep (or Sleep Quality)

Sleep quality is subjective, meaning it is based on the patient (or parent) report of “good” or “poor” sleep.

So what do most people think about when asked if they are satisfied with their sleep?

How much sleep they get

Whether or not they wake up during the night

How they feel upon waking in the morning

Each of these factors overlap with other dimensions of sleep health, but only a patient/parent can determine what a “good” night of sleep means to them.

*The PROMIS Pediatric Sleep Disturbances measure can screen for sleep quality in your patients in as few as four questions.

Because of the subjective nature of sleep quality, you might find in your practice that two families have children who both wake once during the night (or wake too early, or go to bed too late, etc.), but one family finds this to be a problem and the other family does not. The question “do you (or does your child) have a sleep problem?” or “is there something you would like to change about your (or your child’s) sleep?” can help you decide whether further assessment or intervention is needed. It is also important to remember that a parent’s report of their child’s sleep quality may be influenced by the parent’s mood, beliefs, or sleep quality.

* As children get older, parents become less involved with sleep, and may not be aware of a child’s sleep quality. Thus, it is important to ask kids and adolescents directly about their sleep quality. Most typically developing children 8 years can report on their sleep quality starting around 8 years old.

Alertness During Waking Hours

Feeling awake and alert during the day is a strong indicator of good sleep health. Daytime sleepiness can be caused by many factors, including not getting enough sleep, poor quality sleep, or a sleep disorder such as sleep apnea.

Like other aspects of sleep health, daytime alertness/sleepiness differ across development:

Napping is developmentally-appropriate for infants, toddlers, and preschoolers.

School-aged children (6-12 years) should not be regularly napping or falling asleep at inappropriate times (e.g., during school, social events, while eating).

Adolescents may require a short (<45 minute nap) in the early afternoon due to insufficient sleep caused by the intersection between a delayed internal clock and early school start times. But long duration or late afternoon/evening naps can interfere with sleep onset.

*The PROMIS Pediatric Sleep-Related Impairment measure can screen for sleep quality in your patients in as few as four questions.

Daytime alertness can also be impaired by chronic illnesses and mental health disorders. Further, it is important to differentiate between tired/fatigue and sleepiness.

*Ask if a child or adolescent were to lay down in a dark room would they be unable to get up because they feel too tired or would they fall asleep? The former is a sign of tired/fatigue and the latter a sign of sleepiness.

Timing of Sleep

The timing of sleep is when sleep occurs over the 24-hour day, which is usally asleep at night and awake during the day. But of course it is not that simple, as both biological and environmental factors contribute to when children and adolescents sleep.

The circadian rhythm (or internal clock) is the strongest intrinsic factor that determines when we are physiologically sleepy. The strongest cues for the circadian rhythm are darkness (which tells our brain to produce melatonin, preparing our body for sleep) and light (which tells our brain to stop making melatonin and wake up).

Infants do not develop a circadian rhythm until around 12 weeks of age. Thus, young infants have no differentiation between night and day.

With puberty, the timing of the melatonin release is delayed by 1-2 hours for most kids, meaning adolescents are physiologically not sleepy at the early bedtime they once had.

*Even with the developmental changes to the circadian rhythm, bedtimes should not be a free for all! Parent set bedtimes have been shown to benefit adolescent sleep and mental health.

But sleep timing is not all about biology. Early school start times are the strongest factor determining weekday wake time for school-aged children and adolescents, and a significant contributor to insufficient sleep duration.

*Having a consistent bedtime and wake time every day is one of the most important things to ensure healthy sleep. On weekends, bedtimes and wake times should not be delayed by more than 1-2 hours. Otherwise children and adolescents will experience social jet lag, with their internal clocks moving across time zones, even if they never leave the house!

Sleep Efficiency

Sleep efficiency includes how long it takes a child to fall asleep, as well as how long they are awake during the night. Even sleep professionals don’t have a great sense about what age kids can reliably report on their own sleep, but truth be told, there are many adults who also cannot accurately report on this!

As children get older, parents become less involved with sleep routines, and older children/adolescents are less likely to wake parents in the middle of the night, so it is always important to directly ask kids about how long it takes to fall asleep at bedtime, and whether they wake during the night.

For infants and toddlers, it is important to remember that night wakings are normal. Young children have physiological arousals every 50-60 minutes. Most of the time they simply put themselves back to sleep. But if an infant or toddler does not learn to fall asleep independently at bedtime (e.g., parent rocks, nurses, or lies next to child), these young children will likely signal their parent/caregiver to help them return to sleep following normal arousals.

*Sleeping through the night is not well-defined. Different studies have defined it as midnight to 5:00 am (which is not a cheerful thought for new parents) or 8 hours of uninterrupted sleep over the night. However, one paper suggested that the most developmentally valid and socially acceptable definition is from 10:00 pm to 6:00 am, which is achieved by most full-term, healthy infants around two to three months of age.

Sleep Duration

Sufficient sleep duration, or the number of hours one sleeps, is one of the most important aspects of sleep health. We know sleep duration is directly related to physical, psychological, social, cognitive, and academic outcomes across development.

Unlike adults, however, the recommended amount of sleep in pediatrics changes with each developmental stage. Even more striking, the range of sleep duration for each age group is notable, with one study highlighting that normal sleep can sometimes fall outside the recommended ranges.

Asking the following questions in your practice and help determine if a child is getting enough sleep based on their individual needs:

If your child sleeps longer or shorter than usual, do you notice a change in their mood or behavior? (moodiness, irritability, hyperactivity, and lethargy are the first things parents tend to notice when their child doesn’t get enough sleep)

Is your child really difficult to wake in the morning? (I mean really difficult to wake, like sleeping through multiple alarm clocks, needing a parent to throw water on the child)

Does your child fall asleep during school or other inappropriate times (e.g., social events)?

*One way to tell how much sleep a child needs is to have a set bedtime every night for at least one week (preferably during the summer or school break), with no required wake time. The first few nights give them time to catch up on sleep debt, and by the end of the week, the child should begin to wake around the same time every day, telling you how much sleep they need.

Like diet and exercise, sleep is a pillar of health. So it is time to make sleep health a priority for all children, adolescents, and their families! A few simple questions in a clinical setting can help providers quickly identify poor sleep health, as well as provide basic suggestions on how to improve sleep health across development.

Want to learn more about pediatric sleep for your clinical practice? Nyxeos offers provider consultation, live webinars, and an on demand course. Or set up a free consultation to see how we can provide services that meet your needs.